This article summarizes my contributions in the field of computational mechanics during (first-part of) my graduate studies at National University of Singapore (NUS). My work resulted in development of a novel multi-scale computational homogenization framework for composite and auxetic structures. For this novel contribution, I achieved a Best Student Paper Award during the 2017 American Society of Civil Engineers EMI Conference in San Diego. To date, this work have been published in two top journals in mechanics, namely Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids (JMPS) and Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering (CMAME).

Background

A broad spectrum of problems, ranging from the design of innovative composite materials to the modelling of complex structural systems, exhibit multi-scale characteristics. For instance, the mechanical response of a heterogeneous material (e.g. composites, foams and polycrystals) is highly dependent on the underlying microstructural characteristics e.g. morphology, spatial distribution, material and interface properties. A predictive analysis of such materials can be achieved by performing direct numerical simulations (DNS), where the microstructural details are explicitly modelled with a mesh discretization of sufficient resolution. However, such comprehensive analyses are seldom practical for a typical engineering problem due to their inherent high computational costs.

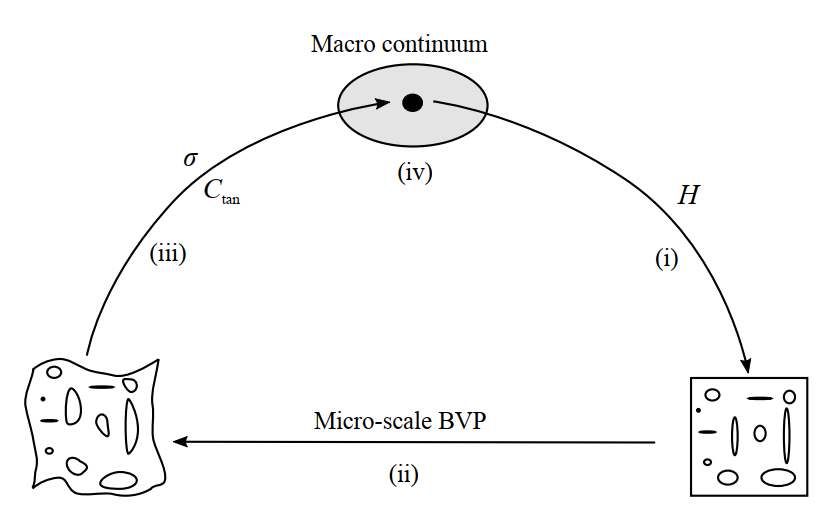

The first-order Computational Homogenization (CH) approach provides a reasonable compromise between accuracy and efficiency. It is a bottom-up formulation that extracts the homogenized material response on the fly, from a Representative Volume Element (RVE) underlying each macroscopic material point. The strategy for first-order CH approach is shown in Fig 1.

First-order CH is a highly predictive approach since no constitutive assumptions are required at the macro scale. This method, however, is restricted to problems where the macro characteristic length scale is much larger than a micro length scale characterizing the micro-processes. This condition is violated in many situations:

- the characteristic structural size is of the same order of magnitude as the underlying microstructure, e.g. in Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS);

- the characteristic loading wavelength spans across only a few microstructural cells, e.g. in micro-indentation experiments;

- the macroscopic deformation localizes into narrow bands that transverse across only a few microstructural cells, e.g. during strain softening.

Motivation

In the absence of a clear separation of length scales, a higher-order enrichment is required to capture the influence of the underlying rapid fluctuations, otherwise neglected in the first-order framework. To this end, we first propose a novel CH framework, where standard continuum models at the micro scale translate consistently onto the macro scale, to recover a generalized micromorphic continuum. Through this contribution, we have achieved the following research objectives:

- developed a predictive CH framework for situations without a clear separation of length scales;

- ventured into the regime of significant material and geometrical nonlinearities, where many existing homogenization theories are inadequate;

- resolved many limitations of the first-order CH framework;

- improved on existing higher-order homogenization techniques;

- reduced the computational cost by three folds adopting a parallel computing algorithm.

Strategy

The homogenization framework follows a bottom-up strategy based on the concurrent coupling of micro and macro-scale Boundary Value Problems (BVPs), as depicted in Fig. 2, which entails the following

(a) defining two macro kinematic fields ($H$ and $\widetilde{H}$) such that the dominant micro-mechanisms are captured;

(b) decomposing micro kinematic fields in terms of their macro counterparts;

(c) imposing the Hill–Mandel condition to effect a consistent transition from micro to macro, thereby extracting the homogenized governing equations;

(d) translating kinematic fields from macro to micro, to define the micro BVP of the underlying RVE. The relevant homogenized stresses and tangent operators are next extracted from the RVE, which are translated back to the macro-scale to complete the coupling between the two scales.

For details on these steps please refer to the references included at end of this article.

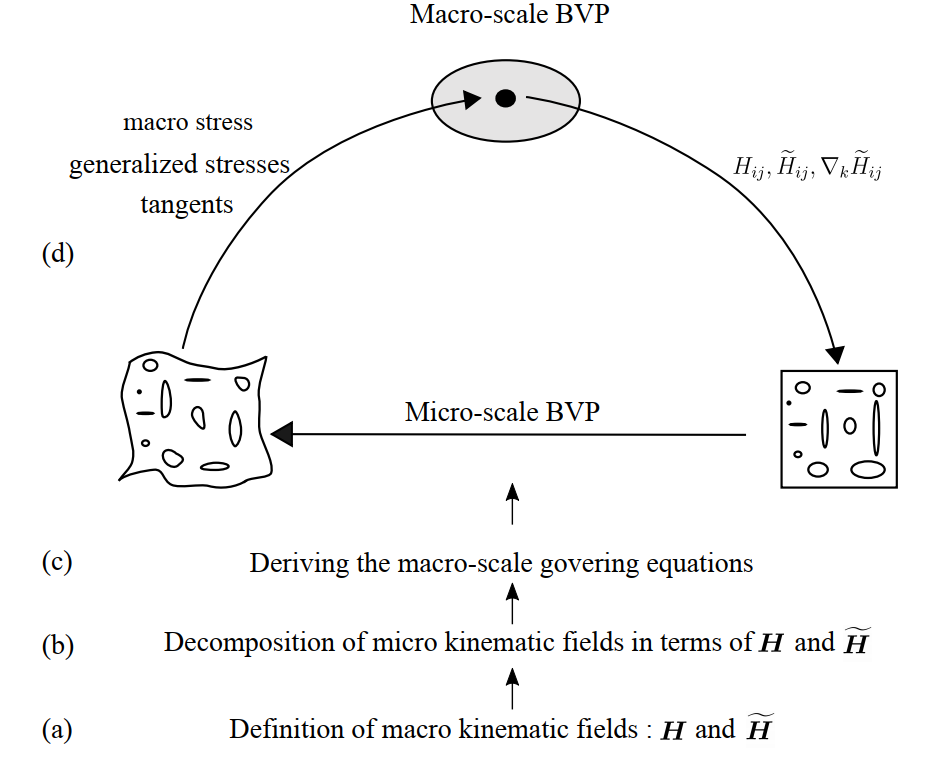

Algorithm

The micromorphic model is implemented by adopting a nested solution scheme, as illustrated in Fig 3, where the macro and micro-scale BVPs are solved concurrently using the Finite Element (FE) method. In this study, the two-scale analysis is seamlessly carried out by integrating the FE code architecture in MATLAB and ABAQUS. The macro-scale BVP is solved using MATLAB to take advantage of the in-built parallel computation model, whereas the micro-scale BVP at the each integration point is resolved in ABAQUS. A python script is invoked to enable a seamless transfer of data between the two scales on the fly. As indicated in Fig. 3, the numerical implementation involves three modules, which entails

- Establishing the FE framework for the macro-scale BVP;

- Solving the micro-scale BVP in ABAQUS with the imposition of kinematic constraints;

- Connectivity between the two scales through the transfer of kinematic information from macro to micro, and the extraction of tangent stiffness and stress tensors from micro to macro.

Numerical Examples

Sinusoidal wave loading

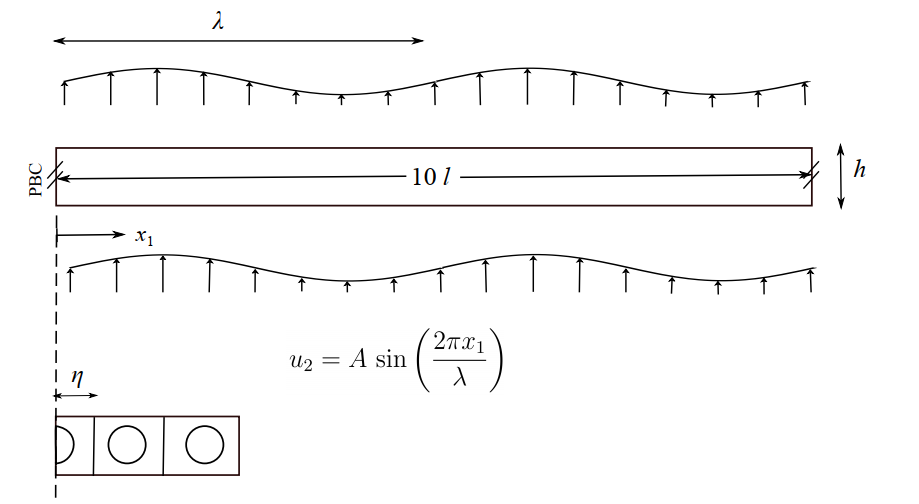

The applicability of the proposed micromorphic framework in situations without a strong separation of length scales is investigated with this example. We consider an infinitely long composite plate of height $h$ subjected to a sinusoidal shear deformation, as illustrated in Fig. 4. In the following, a plate segment comprising of 10 RVEs is considered, with periodic boundary conditions imposed at the vertical surfaces. At its top and bottom surfaces, the displacement boundary conditions are prescribed as

$ u_1 = 0, \text{ } u_2 = A\text{sin}\left( \frac{2\pi x_1}{\lambda} \right) $,

with $\lambda$ and $x_1$ denoting the loading wavelength and horizontal coordinates respectively.

We consider two load cases where the characteristic micro and macro length scales are of a similar order of magnitude ($O(\lambda) \approx O(l)$):

- Case 1: $A = 0.01l, \lambda = 10l$,

- Case 2: $A = 0.005l, \lambda = 5l$.

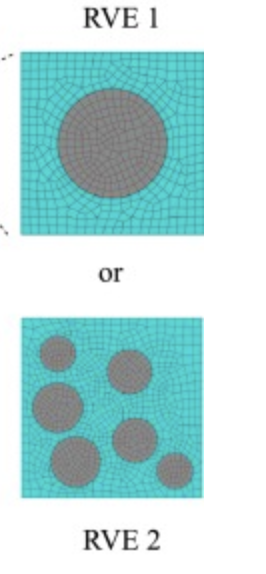

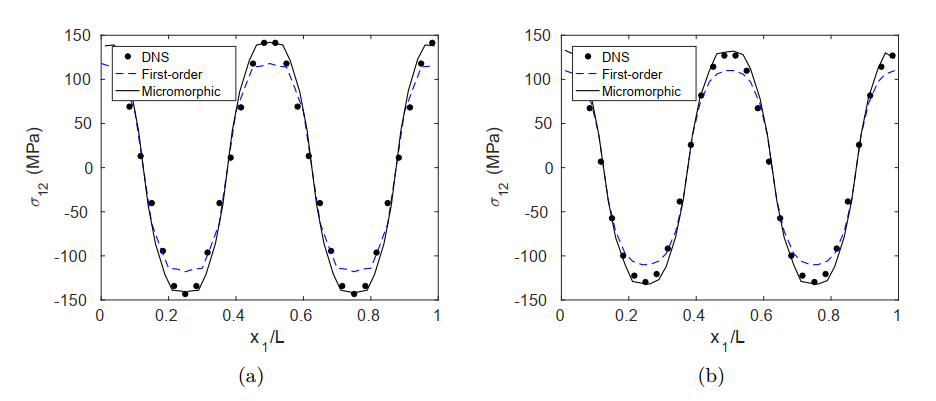

For load case 1 with a weak separation between the two characteristic length scales ($\lambda = 10l$), the first-order CH method provides a reasonable estimate with an error in the range of $∼5\%$ for the two RVEs considered, as depicted in Fig. 5.

In both cases, a small, but observable improvement is obtained with the micromorphic framework. The results suggest that in the regime of a weak scale separation between micro and macro, the nonlocal interactions between the phases already have a non-negligible influence on the overall response.

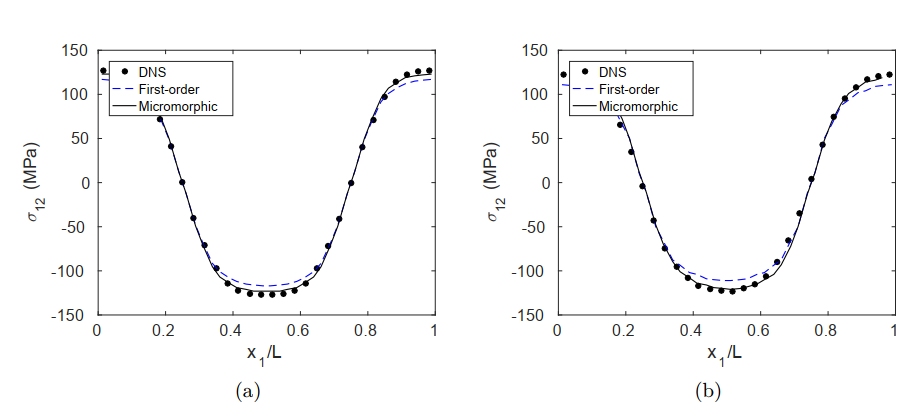

This nonlocal effect is further amplified in load case 2, where a scale separation no longer exists with $\lambda = 5l$. Accordingly, the first-order approach becomes inadequate, with a prediction error of ∼16%, as shown in Fig. 6 for the two RVEs considered. In contrast, the micromorphic approach continues to predict an accurate structural response for the two morphologies, due to an adequate characterization of the underlying rapid fluctuations.

Composite plate with non-uniform cross-section

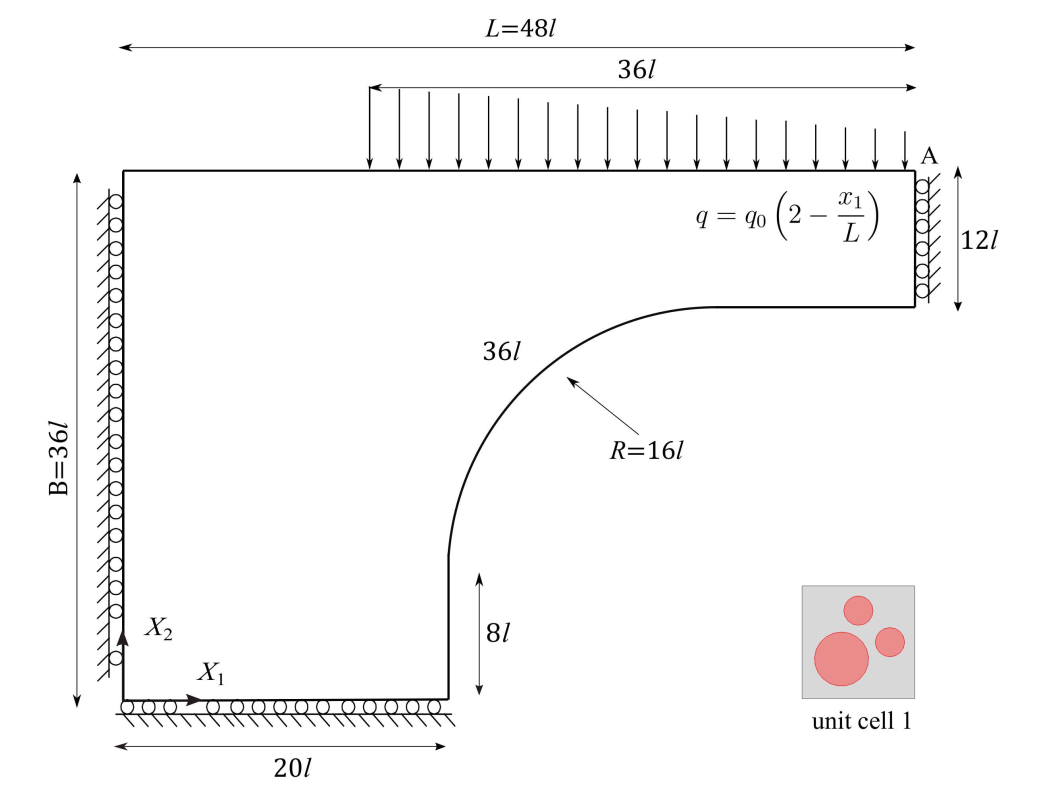

To demonstrate conclusively the predictive capability of the micromorphic model, we next consider a composite plate with a non-uniform cross sectional area in plane strain condition, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

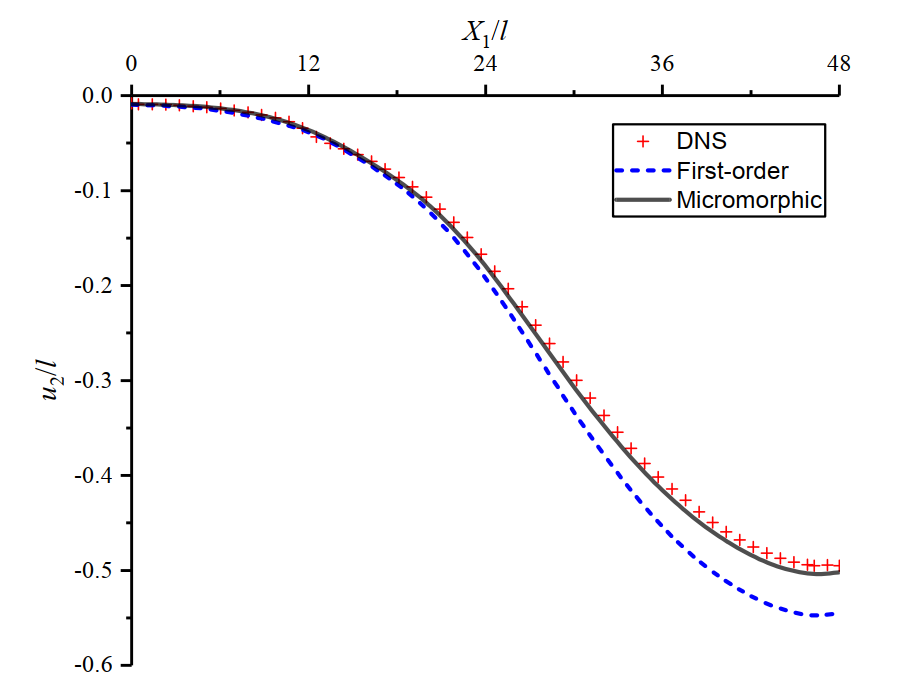

The deflection of the top surface of the plate is depicted in Fig 8. The first-order solution is clearly inadequate, while the deflected shape obtained with the micromorphic approach matches closely with the reference DNS solution.

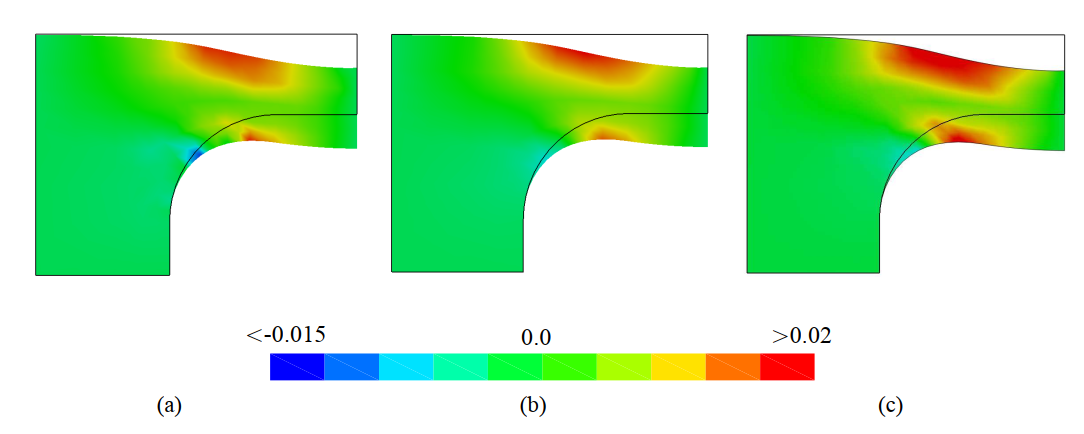

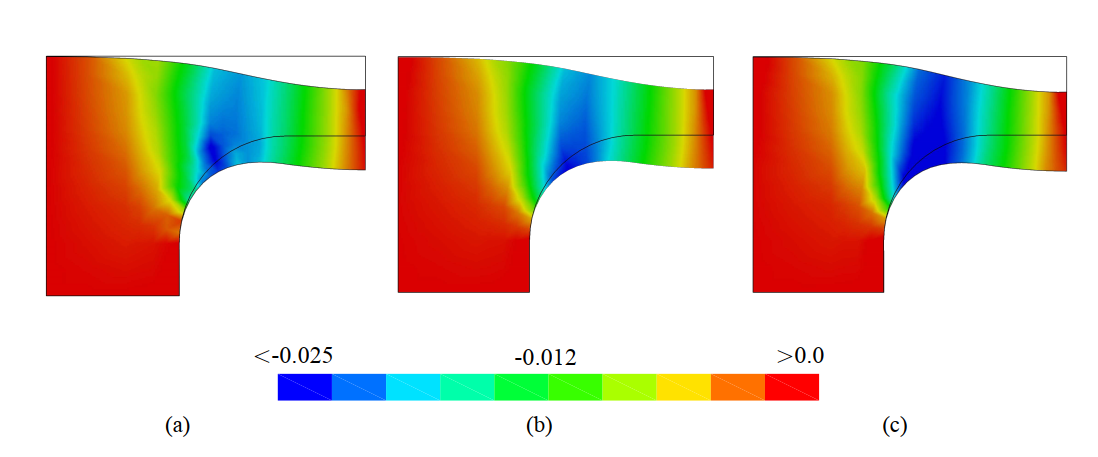

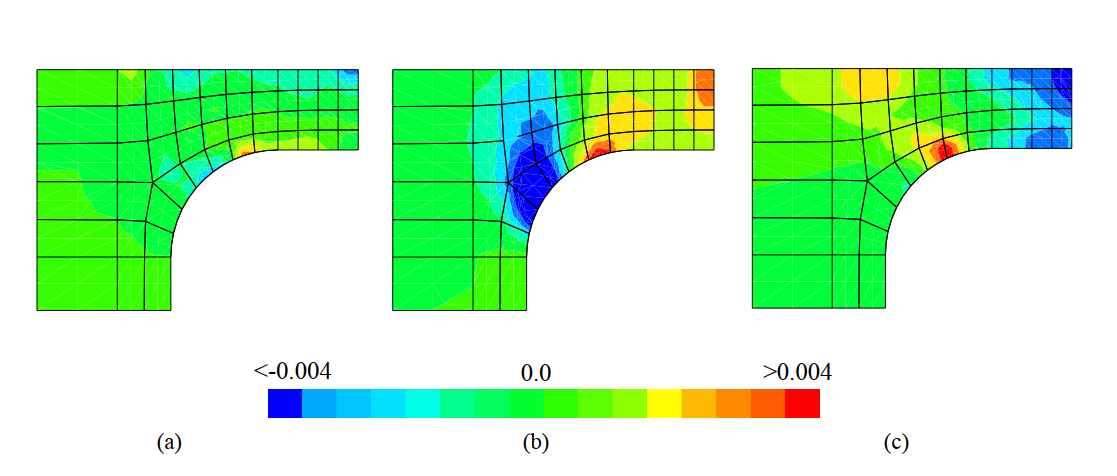

The superior performance of the micromorphic framework is further demonstrated in Fig. 9 and Fig. 10, with deformation gradient contours matching closely the homogenized profiles from DNS solutions. It is apparent that the first-order approach predicts higher values of the shear deformation gradient in the process zone, which leads to an over estimation of the plate deflection in Fig. 8.

c) first-order CH approaches.

c) first-order CH approaches.

The spatial gradients of the morphic variable, depicted in Fig. 11, show a significant contribution from the shear gradient ($\nabla_ 1 {\widetilde{H}_{21}}$) and bending mode. This example thus demonstrates the capability of the micromorphic model to accurately capture the complex interactions between the gradient modes.

c) bending curvature.

Shear localization

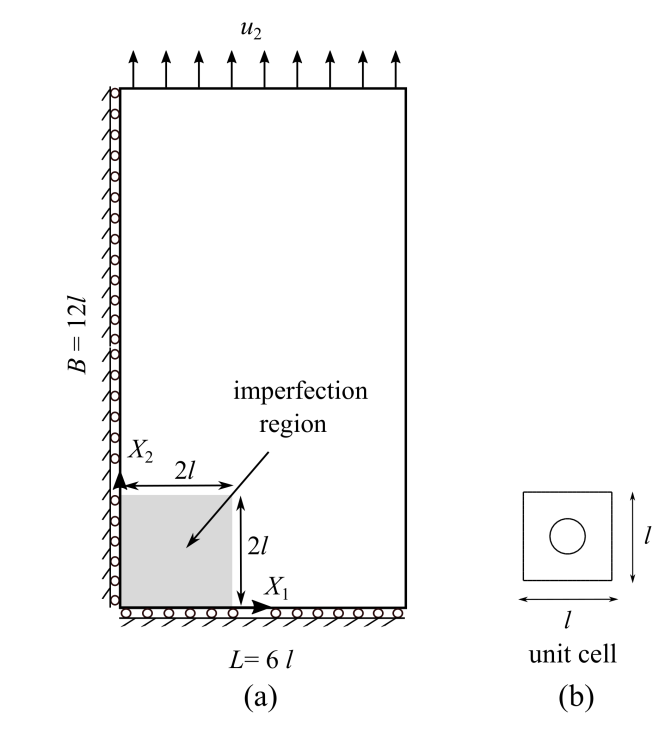

Finally we consider the localized deformation of a perforated plate. The plate consists of 6 × 12 unit cells, as shown in Fig. 12. The microstructure is represented by the unit cell with a central circular void having a volume fraction of 12.5%. The matrix material is assumed to be elastic–perfectly plastic. Within the imperfection zone in the plate, the yield stress of the matrix material is reduced by 20%. A uniform tensile displacement ($u_2$) is prescribed on the top surface of the plate. Roller boundary conditions are applied at the left and bottom edges. At the onset of plastic deformation, the imperfection region will initiate the development of a localized shear band. Beyond this stage, an intense localization band develops in the large deformation regime.

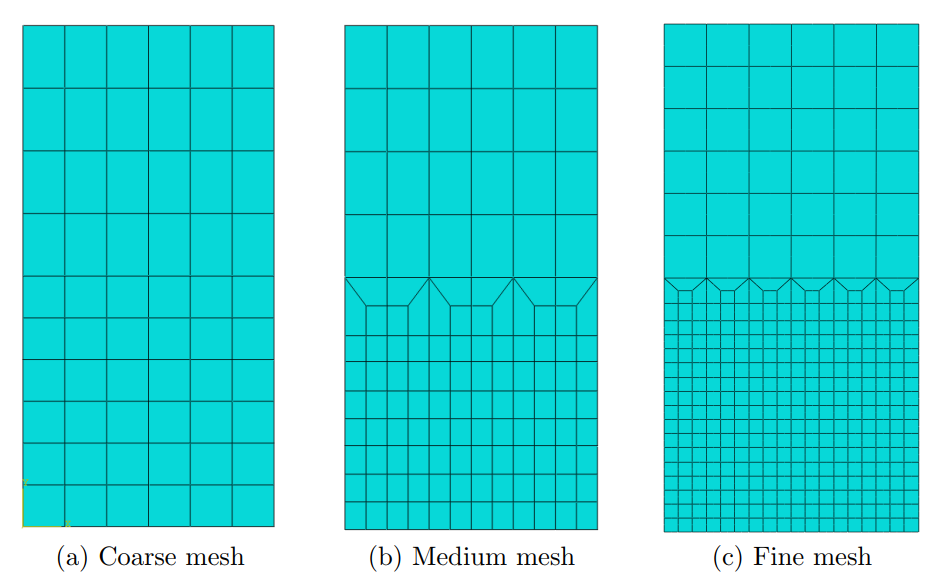

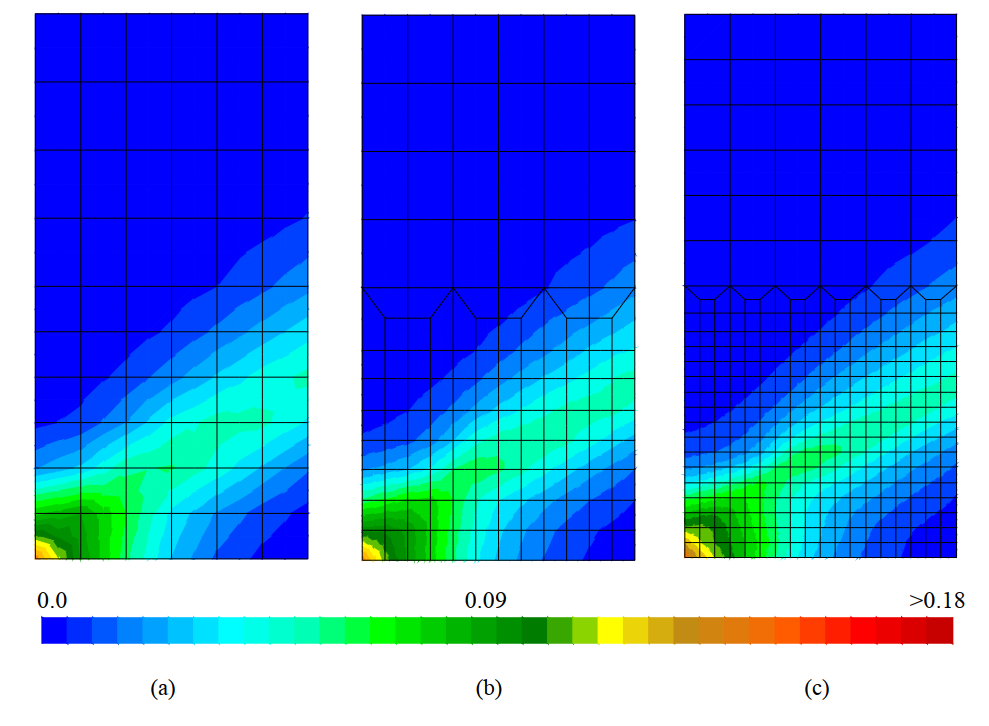

The problem is first analyzed using DNS to establish the reference solution, and solved again with the first-order and micromorphic CH approaches. In order to study the issue of mesh-dependency, three finite element discretizations of the macro domain are considered in the multiscale simulations, as shown in Fig. 13.

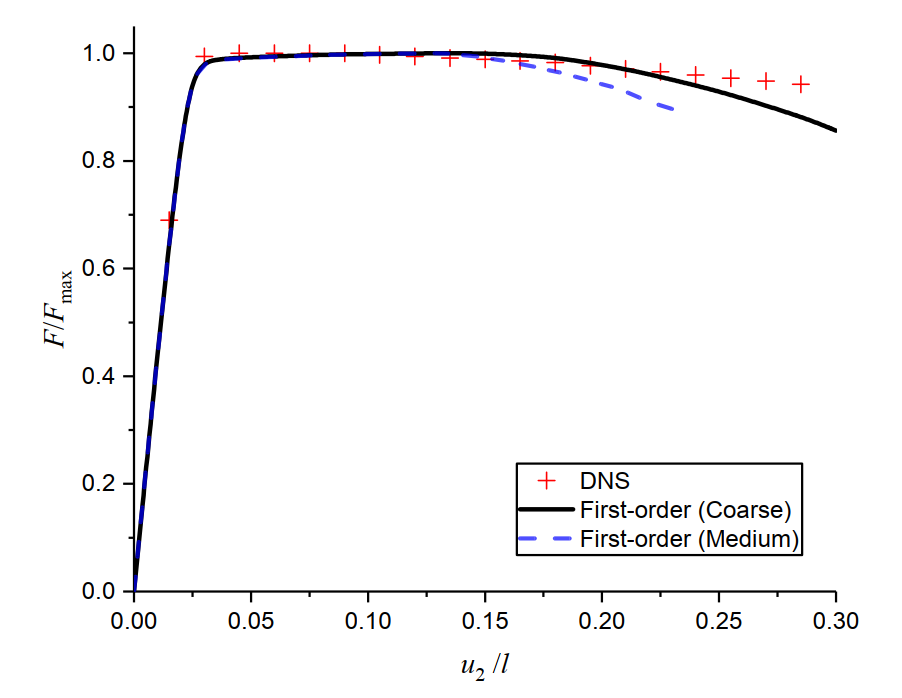

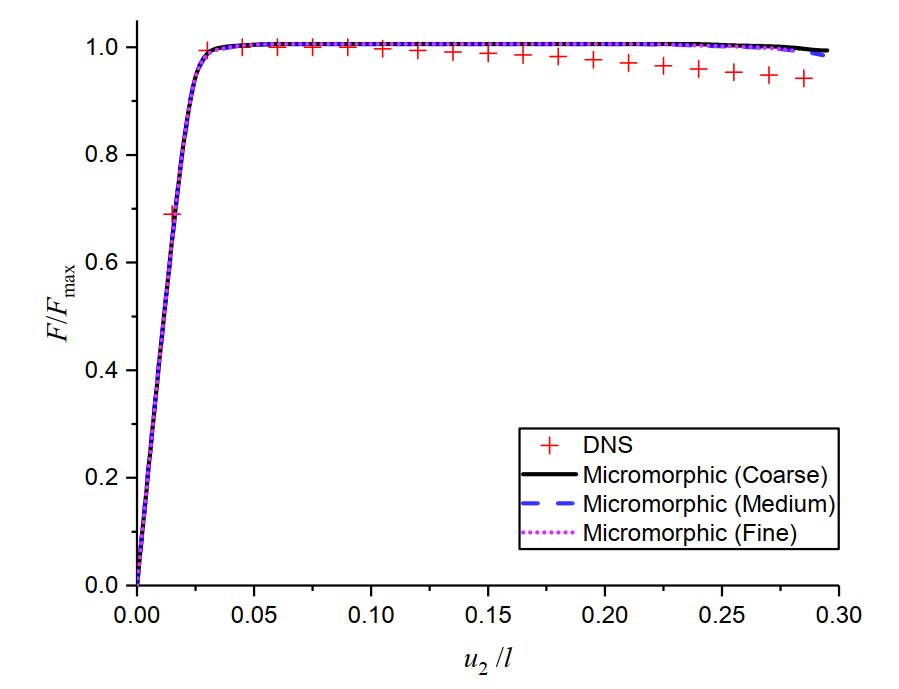

The force–displacement responses obtained from the first-order and micromorphic CH approaches are presented in Fig. 14, Fig. 15 respectively for the finite element discretizations considered. As observed, the structural response of the plate is well predicted by both homogenization approaches at the initial stage. However, mesh dependency becomes apparent in the first-order solution when geometrical softening develops. The resulting macro deformation localizes into a narrow shear band which spans across only a few unit cells, thereby violating the separation of scales assumption. Furthermore, the first-order simulations stop before completion, due to an excessive deformation developed in the process region.

The micromorphic approach remedies the limitation by incorporating a length scale parameter that characterizes the interaction between inclusions, associated with the gradient of the morphic field. The proposed homogenization framework thus regularizes the geometrical softening response. The deformation gradient profiles obtained with the micromorphic framework, depicted in Fig. 16, furthermore demonstrate the regularization property. The mesh independent solutions obtained with the micromorphic framework, however, are slightly stiffer than the reference DNS solutions.

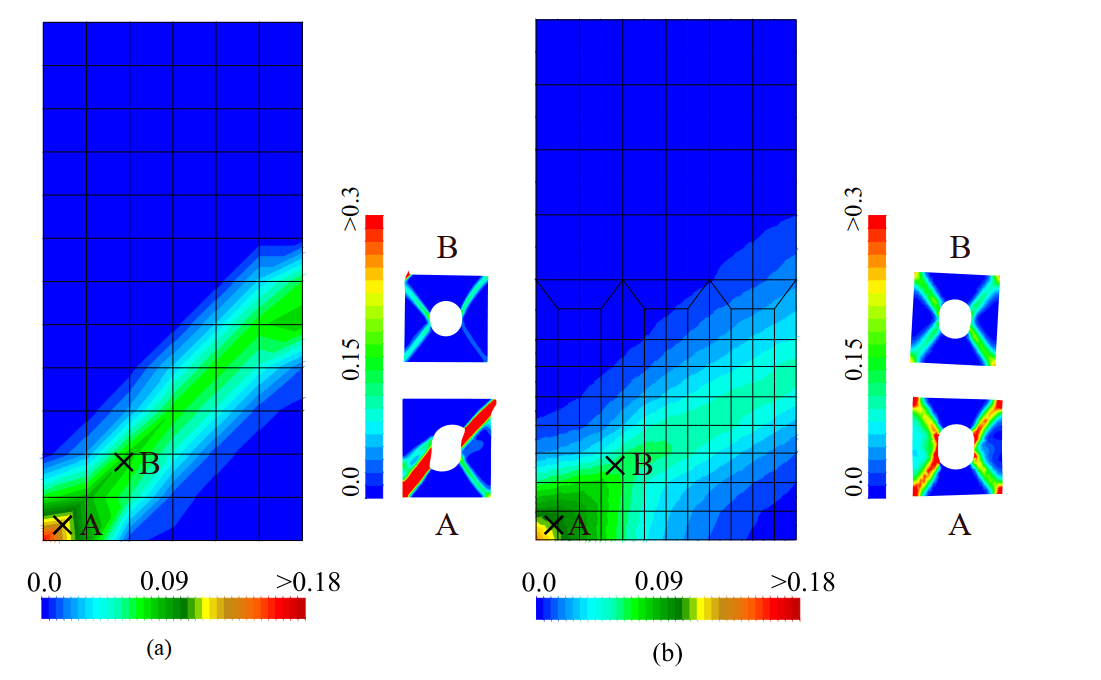

c) fine mesh.

Further insights into the localization problem are obtained by investigating the micro-processes within the shear band during geometrical softening. Fig. 17 depicts the homogenized axial deformation gradient ($H_{22}$) extracted from the DNS by taking the volume average over each unit cell. It is easily observed that the shear band develops at a smaller angle with the micromorphic framework. Referring to the deformation characteristics of two unit cells located within the shear band, it is evident that the generalized PBC in the micromorphic framework induces a pathological deformation mode in the underlying unit cells during geometrical softening. Due to the periodicity requirement, a localized band cannot develop within the unit cell, hence departing from the actual mechanism obtained in DNS. This over constraint thus results in a stiffer response with the micromorphic approach in Fig. 15. To remedy the limitation, the percolation-path-aligned boundary conditions can be adopted during softening.

Conclusions

This article presents a novel CH approach that consistently translates standard continuum models at the micro-scale onto the a generalized micromorphic continuum at macro scale. The proposed framework introduces an additional macro kinematic variable to characterize the micro-mechanism underlying a rapidly fluctuating response. The net effect of resulting microstructural fluctuations is propagated to the macro-scale via the Hill-Mandel condition, which in turn provides the definition of macro stress and the generalized stress tensors.

The excellent predictive capability of the proposed homogenization model is demonstrated with three numerical examples. The first example demonstrates the applicability of the proposed homogenization framework even in the absence of a clear separation between the loading wavelength and the unit cell size. In this regime considered, the nonlocal interactions between different underlying mechanisms induce an overall size effect at the macro-scale. This is captured naturally by the proposed micromorphic approach via the internal length scale parameter associated with the higher-order morphic field. Second example illustrates versitility of the proposed framework to capture structural responses, when compelx interations among the spatial gradients become significant. Finally, the regularizing capability of the micromorphic CH framework is demonstrated via a strain localization problem with geometric softening. The force–displacement response and homogenized deformation gradient profiles obtained with the micromorphic approach are shown to be mesh independent.

References

- Biswas, R., & Poh, L. H. (2017). A micromorphic computational homogenization framework for heterogeneous materials. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 102, 187-208.

- Biswas, R., Shedbale, A. S., & Poh, L. H. (2019). Nonlinear analyses with a micromorphic computational homogenization framework for composite materials. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 350, 362-395.